Cozy English villages teeming with ‘Midsomer Murders’

Mystery Scene, Spring 2020

Quaint villages shadowed by secrets. A roster of eccentrics. Murders most bizarre. Not to mention all those teapots and taverns.

During its 20-plus years on TV, “Midsomer Murders” has quietly staked out its own territory – think of it as Agatha Christie with a dash of “Twin Peaks” – and in doing so, it has quietly become a genre classic. Circumventing casting changes and controversy, the popular British series has attracted viewers the world over – in some 200 countries to date.

Not bad for a contemporary crime drama about cops without guns. (Unlike US police officers, the majority of UK police do not carry them.)

Inspired by the Inspector Barnaby books by Caroline Graham, the series is set in fictional Midsomer County, where veteran Detective Chief Investigator John Barnaby – who took over when his cousin, Tom Barnaby, retired – probes mysterious deaths that occur in the county’s quirky, picturesque villages.

Of course, all is not what it seems within those villages. Which is why the media pokes fun about life in Midsomer. Per the British newspaper, The Telegraph, the county’s average life expectancy “can be compared unfavorably with Al Capone’s Chicago.”

Now in its 21st season – a feat paralleled in this country only by the turgid and hectoring “Law and Order: Special Victims Unit” – the UK series is now streaming on BritBox and Acorn TV. The new season debuted in December while several older seasons continue to be available on local PBS stations. And of course, the many seasons (excluding the latest) are available on DVD.

Sabine Schreiner is co-author (with Joan Street) of “Midsomer Murders on Location” (Baker Street Studios Limited) and president of the Midsomer Murders Society, a fan group that hosts several annual events that draw attendees from as far away as the U.S. and Australia. When asked about the show’s appeal, Schreiner lists a number of factors. Early on, she says, it was the stars who enticed viewers – especially leading man John Nettles, who played DCI Tom Barnaby for 13 seasons (81 episodes). Neil Dudgeon now portrays DCI John Barnaby, Tom’s younger cousin.

Aiding and abetting the DCI is a series of young sidekicks. Nick Hendrix now carries the badge as DS Winter.

Notable guest stars are also an attraction. The “who’s who” has included former Disney star Hayley Mills, a pre-“Outlander” Sam Heughan, Oscar winner Olivia Colman, Henry “Superman” Cavill, Bond girl Honor Blackman and rock ‘n roller Suzi Quatro.

Schreiner also cites the classy production values: “Superb actors, scriptwriters, directors … sets it apart from other TV series, and goes a long way in explaining the show’s longevity,” she says.

Then there’s the notion that familiarity breeds comfort. Sue Turnbull, author of the book “The TV Crime Drama” (Edinburgh University Press), points out that viewers can settle down with “Midsomer” knowing full well that it will deliver “eccentric characters in twee settings, an unlikely murder, and a successful investigation.” As a Brit who has spent half her life in Australia – she is a professor of communications and media studies at the University of Wollongong – she adds, “the aesthetics of the form offer me a familiar security blanket.” It is, she says, “an idea of England that I find very nostalgic.”

Anthony Horowitz, the dizzyingly busy author-producer who helped originate the series, giving it its name and creating its bible, sees “Midsomer Murders” as an antidote to today’s uneasy headlines. “I think particularly now, with so many difficulties surrounding politics and the media, people look back very nostalgically on an England that consisted of smaller, quieter communities where everyone knew everyone and life was simpler.”

The investigators are based in the “county town” of Causton, home to Causton CID – that’s the Criminal Investigation Department, the Brits’ way of saying a police department. The quaintly named fictional villages of Midsomer County include Midsomer Newton, Aspern Tallow, Midsomer Mallow and Badger’s Drift – nods and winks to the mystery subgenre, the cozy. The population of Midsomer County goes through a lot of tea and coffee. Tea rooms are everywhere. And each village has its pub.

For non-UK viewers, some translation may be required. If someone’s got form they’ve got a record; if someone’s losing the plot they’re losing their mind. You don’t want to be called a fishwife, an odious sod or a toerag (ewww!). A toodle-pip! is a cheery send-off.

Storylines are rife with feuds (some dating back centuries), fights over money and property, and tangled relationships.

The delivery is old-fashioned in the sense that there’s no cursing or explicit sex or violence. There have only been snippets of nudity. Several times they involved young women posing for artists, though two episodes with Jason Hughes, as Detective Sergeant Ben Jones, got cheeky – showing his bare backside (once while he was singing in the shower).

Did we mention that the handsome young sergeants – who have always been single, and romantically available – come and go?

Meantime, and obliquely, “Midsomer” subverts the crime-drama genre.

When a film crew descends on Midsomer Magna, for a movie about the French Revolution (season 10’s “They Seek Him Here”), the unhappy producer bellows, “Not enough peasants … for future scenes you’ll need more crones and hags.” But, “Don’t make hard work of it … an area like this must be overrun with yokels and inbreds. Why don’t you try the local old-folks home? They’ll come cheap.” In a later scene a bus from the retirement home pulls into view. Ouch!

Over the years, the show has become famous for the increasingly bizarre ways in which it offs its victims.

An astronomer is bludgeoned with a meteorite. A cook drowns in a cauldron of soup. A butterfly collector is pinned to a wall. A dotty elderly woman dies when a tower of newspapers (the UK’s Daily Telegraph) topples over her. A man staked to a lawn by croquet wickets is killed by catapulted wine bottles. Then there was the woman who was crushed by a large wheel of cheese. (“Hard cheese?” asks the investigator.) One poor bloke was tied to a tree, covered in truffle sauce, and eaten by wild boars.

“It’s like you are in the woods and you find some beautiful log and turn it over and all the woodlice, spiders and beetles come running out from underneath,” is how star Neil Dudgeon once described the nastiness hidden in the shadows of the scenic settings.

“It’s like you are in the woods and you find some beautiful log and turn it over and all the woodlice, spiders and beetles come running out from underneath,” is how star Neil Dudgeon once described the nastiness hidden in the shadows of the scenic settings.

Compared to the various suspects they come across, the investigators are rather ordinary. Which is by design.

Author Caroline Graham once said of Tom Barnaby: “[He] is a straight, happily married middle-of-the-road copper. He’s strong but he’s not intensely charismatic or eccentric in any way.”

Graham, who is now in her late eighties (and was unavailable for an interview) has a colorful CV that, briefly, goes like this:

She worked in a textile factory at age 14 (at three shillings a week), joined the Wrens (Women’s Royal Naval Service) at 17, later attended ballet school in France, followed by multiple odd jobs.

Married (and later divorced), with one son, she was in her late thirties when she heard a library talk by popular crime writer Christianna Brand. Brand was known for books including those featuring Inspector Cockrill of the Kent County Police.

As Graham has recalled, “[Brand] was superb and everything I thought a writer should be. She was wearing brocade, fur, a hat and had a cigarette in a long holder.” After hearing her, Graham wrote a story and sent it to her. An encouraging reply led to Graham’s decision to take a creative writing class. She went on to write radio plays and, during the late Seventies, episodes of the British TV soap opera, “Crossroads.”

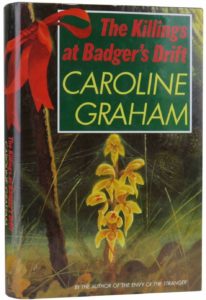

Turning to books, she wrote a romance, then segued to horror. Teamed with her son, she wrote several children’s titles. But crime was what was popular. And so, she wrote “The Killings at Badger’s Drift,” the first title to feature DCI Tom Barnaby. Published in 1987 in the UK, it features plenty of traditional British touches – tea carts and the like. But it also has a skewed sensibility. It opens with an elderly spinster walking through the woods, in search of a rare white orchid. She chances upon something else, and winds up dead. A tangle of blackmail, incest and off-center characters follows.

When it was published in the US in 1988, Publisher’s Weekly called the book “uncommonly appealing … a real winner.”

Graham certainly was in esteemed company when the book was named to the Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time, per the UK Crime Writers’ Association (in 1990). The roll call included Josephine Tey’s “Daughter of Time,” Raymond Chandler’s “The Big Sleep,” Agatha Christie’s “And Then There Were None,” Dashiell Hammett’s “Red Harvest” and P.D. James’s “Innocent Blood.”

“Badger’s Drift” also won the Macavity Award for best first novel, was nominated in the same categories for the Anthony and Agatha awards, and was included in the 100 Favorite Mysteries of the 20th Century, as selected by the Independent Mystery Booksellers Association.

In all, there are seven Chief Inspector Barnaby books. According to Graham’s agent, Anthony Goff, the books have sold in 20 languages in addition to the UK and US. (In the US, the first four titles are published by Felony & Mayhem Press; books five through seven are with Minotaur.) “That translation figure is very good for a crime series,” says Goff, “but the TV series has never had the effect on books sales in the UK (nor, I think, in the U.S.) that you might have expected. This is perhaps because the tone of the novels is quite dark whereas the TV is much cozier.” But, he adds, “[Caroline] was always quite philosophical about that, and never resentful.”

Ten years after its publication, “The Killings at Badger’s Drift” came to TV. The feature length program aired in the UK in March 1997, with Nettles starring. As the year’s top rated single program, it garnered nearly 14 million viewers.

It didn’t hurt that its star was well known to viewers. Nettles had spent a decade (1981-1991) playing unorthodox investigator Jim Bergerac, in the BBC-produced “Bergerac.” That character was an alcoholic and divorced father who romanced lots of ladies and logged in plenty of chases, both on foot and while behind the wheel of his classic Triumph Roadster.

In contrast, “Midsomer” found the younger Sgt. Troy (Daniel Casey) doing most of the running, while Barnaby stood by, working strictly by-the-book. When not quizzing suspects, he was happily at home with wife and daughter

It was producer Betty Willingale (a veteran script editor and script consultant) who first envisioned the possibilities of Graham’s work for the screen. And she wanted Nettles as Tom Barnaby. “It isn’t a role that goes deep into investigative techniques or forensic analysis … but he does present this very British approach to the role,” Willingale once said, adding, “And that approach is to look largely unperturbed and just carry on.”

“I liked that Barnaby was an ordinary man – and John Nettles played the husband/father perfectly,” says Anthony Horowitz, who wrote the script for “Badger’s Drift,” and four episodes for seasons one and two. They were all directed by the late Jeremy Silberston, whom Horowitz credits with creating “the style” for “Midsomer Murders.” Silberston did the same for “Foyle’s War,” the World War II-set detective series that Horowitz created and wrote. “He had an intuitive understanding of story and always delivered what was on the page – making it beautiful at the same time,” Horowitz adds.

(For more about the prolific Horowitz, author of more than 40 books, including the teen spy series, Alex Rider, and the Daniel Hawthorne mystery series, see the Summer issue #155 of Mystery Scene.)

When “Midsomer” debuted in the U.S. in 1998, Tom Barnaby’s “ordinary man” status was a selling point.

“It’s very refreshing to be in the company of a detective who has a happy marriage and is not dysfunctional,” said Delia Fine, who ushered the show into the country via her tenure at the A&E cable network. Speaking to the New York Times, Fine added, “I get these visions of an endless parade of aging, ex-alcoholic white men in rumpled trench coats, with egg on their ties, who are always in troubled marriages and have problems with authority.”

“It’s very refreshing to be in the company of a detective who has a happy marriage and is not dysfunctional,” said Delia Fine, who ushered the show into the country via her tenure at the A&E cable network. Speaking to the New York Times, Fine added, “I get these visions of an endless parade of aging, ex-alcoholic white men in rumpled trench coats, with egg on their ties, who are always in troubled marriages and have problems with authority.”

The late Fine (she passed away in 2016) was vice president of film, drama and performing arts for A&E when it aired its “Mysteries to Die For” programming umbrella that also included “Hercule Poirot,” “Sherlock Holmes” (the one with the late Jeremy Brett), “Inspector Morse,” and “Miss Marple.” Of the lineup, Fine said, “We have so little resolution in our daily lives … But with a mystery, everything’s tied up at the end. It’s one of the things that makes them so appealing,”

As with any series that’s survived over time there have been challenges that have led to changes. Most notably as a result of a 2011 controversy, when producer Brian True-May gave an interview to Radio Times in which he called the series “the last bastion of Englishness,” saying that the all-white cast – and lack of multiculturalism – was a reason for the show’s success.

The comments led to immediate repercussions. An apologetic statement was issued by ITV, the UK network that airs the show. The head of policy research for the country’s leading race equality think tank penned an opinion piece (for the Telegraph), asking for understanding of diversity experiences. And True-May was suspended from the show. (He later returned.)

Ever since, the ethnic minority population of Midsomer County has grown.

Meantime, there have been shifts in the approach to technology and science. Harkening back to the show’s origins, Horowitz admits, “I was very keen to keep the modern world out of the stories so that they would exist in some strange territory between golden age and the 21st century.” For that reason, there were few pathologists and little forensic science. “Barnaby was on a level playing field with Poirot and Sherlock Holmes,” says Horowitz.

Not anymore. Computers and cell phones and forensics (and a shifting roll call of pathologists) are now a part of CID.

“Midsomer” mania extends beyond the screen. Befitting a show famed for its picturesque, albeit blood-spattered, settings, myriad tours of “Midsomer” location sites are offered.

In fact, the series is credited with boosting the economies of the areas where it films. Workshops are conducted for businesses looking to capitalize on what its organizers – tourism experts – call “the “Midsomer” effect.” (For instance, Lodden Brewery in Oxfordshire, which has appeared in the episodes “Night of the Stag” and “The Ghost of Causton Abbey,” brews a Night of the Stag beer, and conducts tours for “Midsomer” fans.)

Here’s how Brit Movie Tours touts its “Midsomer” outing: “You will visit fairy tale houses, ancient churches, cozy pubs, charming village greens, quaint stores and grand houses that feature prominently in the magical but rather deadly county of Midsomer.”

Like the country’s formidable queen, there’s a sense that “Midsomer” could reign forever. With tea and good manners, “Midsomer Murders” carries on. Toodle-pips and all.

back to writings

back to writings