Just the Facts: Nonfiction Books Reviewed

Mystery Scene, Winter 2022

Curious about the history of mysteries and the folks who write them? You could take a master’s class that spans months and costs serious bucks. Or, you could buy Martin Edwards’ latest genre compendium, and curl up with it on your sofa. But do so with care … the book weighs in at 2.6 pounds.

In The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators (Collins Crime Club, November 2022, 724 pages, $32.99), Edwards gives the reader the full monty with his authoritative, eye-opening and entertaining opus. He is well-qualified to do so, as the archivist of the Crime Writers’ Association, president of the Detection Club, and author of titles including the hefty The Golden Age of Murder: The Mystery of the Writers Who Invented the Modern Detective Story (2015).

Comprised of 55 chapters with endnotes, the final 100 pages devoted to bibliography and indexes, The Life of Crime scrutinizes the genre through changing eras, subgenres, specific writers.

Citing novelist-critic Julian Symon’s 50-plus year-old Mortal Consequences: A History from the Detective Story to the Crime Novel as impetus for this project, Edwards utilizes what he calls “novelistic techniques” – accessible rather than scholarly writing – to chart the genre’s story. Chapters begin with a tantalizing anecdote, which leads to an examination of topic. Many names and claims to fame will resonate with genre enthusiasts. Just as many will surprise.

What was the first book about a manhunt? Long before John Buchan’s masterful The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915) there was Things As They Are: The Adventures of Caleb Williams, written by William Godwin in … 1794. Oh, Godwin gave the genre another benchmark when he and his wife, the pioneering feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, produced daughter Mary, who would go on to pen Frankenstein. Readers of Ruth Rendell will be glad to hear that, as a fledgling journalist, she faked her attendance at an event she was assigned to cover. Writing the piece as if she’d been there, she was unaware the guest speaker had dropped dead at the gathering. Fired from her job, she decided to write a mystery. A chapter on genre rogues gives a nod to Arthur Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law, E.W. Hornung, creator of the debonair A.J. Raffles, cricketer by day, burglar by night.

Naturally, Doyle’s Great Detective gets his own chapter and other usual suspects – among them, Christie, Highsmith, Hammett, and Chandler – are also prominently featured.

But there are also accolades for the offbeat. Like the scientific mysteries of R. Austin Freeman, who personally tested his assorted theories. And how about Astrogen Kerby, aka Astro, the psychic and charlatan who solves crimes in the anonymously published 1912 short story collection The Master of Mysteries. A cipher within the book identified the author as Gelett Burgess who, per an endnote, is credited with originating the term, “blurb.” Yes, some of the book’s details are deliciously arcane.

Edwards doesn’t neglect the challenges of early female crime writers, some of whom felt it necessary to utilize male pseudonyms or gender-neutral monikers. Discussing genre diversity, Edwards charts the talents and turbulent personal life of Black writer Chester Himes, moving on to the impact wielded by the black-Jewish Walter Mosley, and his PI, Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins. The pros and cons of various Asian crime-fighters are also explored, and props given to the first gay detective.

I could go on and on … about the book’s coverage of Scandinavian crime, noir (and more noir), domestic suspense, psychological suspense, police procedurals, even my personal favorite, Ross Macdonald. But if I continued it would become a master’s class, and I’d have to charge tuition. Get this book instead. It’s an essential for mystery lovers.

**

Omitted from the massive Edwards tome, Stephen King merits his own spotlight in the gorgeously produced, oversize volume, Stephen King: A Complete Exploration of His Work, Life, and Influences (Epic Ink, September 2022, 240 pages, $30). Timed to the prodigious writer’s 75th birthday, this celebratory critique is by Bev Vincent, who himself is pretty prodigious. Author of more than 120 short stories (published in Ellery Queen, Alfred Hitchcock, etc.), and previous King-related books, Vincent has been chronicling his idol for more than two decades, actually collaborating with King on several projects.

This book’s focus is on King’s writings, and includes anecdotes about particular works (King’s breakthrough novel, Carrie, began as a short story), as well as manuscript pages, correspondence to and from publishers, book cover art, and more. Interspersed are “sidebar” featurettes on film adaptations, King’s sports interests, collaborations, and so on. Fittingly, some of the book’s pages are “blood”-spattered.

Cynics may think it improbable, but Vincent manages to include appendixes of all of King’s writings (phew!) – and those myriad adaptations, right up to the latest streaming ventures.

This work will delight Stephen King’s fans while giving pop culture scholars – and adventurous newbies – plenty to process.

**

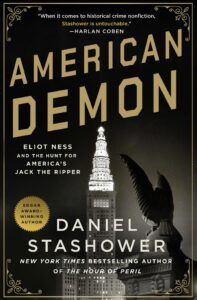

If historical true crime is your passion, reach for American Demon: Eliot Ness and the Hunt for America’s Jack the Ripper (Minotaur Books, September 2022, 352 pages, $29.99), in which Daniel Stashower details the life, career, and eventual downward spiral of the legendary G-Man, whose final years were tinged by regrets about the case he couldn’t solve.

If historical true crime is your passion, reach for American Demon: Eliot Ness and the Hunt for America’s Jack the Ripper (Minotaur Books, September 2022, 352 pages, $29.99), in which Daniel Stashower details the life, career, and eventual downward spiral of the legendary G-Man, whose final years were tinged by regrets about the case he couldn’t solve.

It was as Cleveland’s Director of Public Safety in the 1930s, in the aftermath of helping to take down Chicago’s Al Capone, that Ness was tasked with finding a serial killer who became known by lurid monikers such as the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury and the Mad Torso Killer. To this day, the case remains unsolved.

Part biography, part true crime saga, this work utilizes reams of documents, including Ness’ own papers, and a cavalcade of newspaper clippings. It also builds on previous non-fiction books, including the 2020 entry by genre heavyweight Max Allan Collins and A. Brad Schwartz, and multiple volumes by James Jessen Badal (also an interview source), the Cleveland professor who has spent decades studying and writing about the homicides.

Stashower, a multiple Edgar award-winner, came away from this book still admiring Ness, even though the man wasn’t as stalwart as media depictions by the likes of Robert Stack and Kevin Costner. Still, in addressing the lawman’s failings, Stashower underscores the challenges he faced. With the torso killings, the era’s forensics tools were a serious impediment.

A skilled writer, Stashower delivers vivid, atmospheric depictions of the era and locales. There’s no downplaying the horrific nature of the crimes – even basic details are gruesome. At one point authorities put a severed head on display, in hopes of identifying a victim. No one was ever brought to justice and no conclusive evidence remains, still, Stashower has his suspicions (and they seem solid) about the evil doer. Devotees of true crime, especially the serial killer subgenre, will not be disappointed.

**

I’ll sign off with The First True Hitchcock: The Making of a Filmmaker by Henry K. Miller (University of California Press, January 2022, 233 pages, $26.95), which delves deep within the foggy mythos surrounding the 1927 silent movie, “The Lodger.”

Based on Marie Bellow Lowndes’ classic 1913 novel about a boarding house tenant, who may be Jack the Ripper, Hitchcock’s screen version launched an astounding career – indeed, a brand. Miller, a Sight and Sound critic and author of The Essential Raymond Durgnat (he was an esteemed British film critic), microscopically examines the 26-year-old director’s every filmmaking decision, including the choice of where to stage the first murder – which “marked the real beginning of a film career in which appearances deceive, identities divide, and authorities are undermined.”

Hitchcock’s relocation from Britain to America is ever-shadowed by The Lodger, which he long talked about remaking. Despite the assignment going to another filmmaker (for a 1944 version), Hitchcock was still trumpeting the possibility when he sat down for his famous interviews with French filmmaker-critic Francois Truffaut in 1972.

An academic work that could have used more chronological organization, this book nonetheless fills a gap within existing Hitchcockian studies. That alone makes it worthy of scrutiny. As does time spent in the company of the ever-compelling master of suspense.

##

back to writings

back to writings