The Black Dahlia

The New York Times, February 5, 2006

During her brief lifetime, Elizabeth Short never starred in a single movie. There is no record of her having played so much as a bit part. Yet within popular culture, Short — who frequently told friends she wanted to break into show business — has emerged as something of an honorary leading lady whose shadowy life and violent death follow the contours of a classic film noir script.

During her brief lifetime, Elizabeth Short never starred in a single movie. There is no record of her having played so much as a bit part. Yet within popular culture, Short — who frequently told friends she wanted to break into show business — has emerged as something of an honorary leading lady whose shadowy life and violent death follow the contours of a classic film noir script.

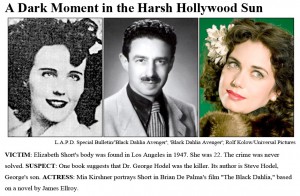

She certainly had the looks. Along with a hubba-hubba figure, she possessed a great smile, alabaster skin and dark, curly hair. And she died right: young, mysteriously and gruesomely. Screaming headlines reporting her murder in 1947 warned of a “werewolf maniac,” as this city’s five newspapers sought to outscoop one another. Photos of her corpse — torso cut in two, face slashed into a hideous mock of a grin — were suppressed.

But the nickname cinched it. It was derived from a popular movie of the day called “The Blue Dahlia,” starring Veronica Lake and Alan Ladd. Short, who at the age of 22 stood out with her black clothing and her dark, sometimes flower-adorned hair, was known to friends as the Black Dahlia.

Obsession has surrounded Short’s murder from the beginning, as a roll call of confessors — there were dozens — stepped forward, claiming they had done the Dahlia in. But to this day the case has not been solved, further adding to the lore. Now, nearly six decades after her death, Universal Pictures is preparing to release “The Black Dahlia,” based on James Ellroy’s 1987 novel of the same title, giving Short her first big-screen close-up. Directed by Brian De Palma and budgeted at about $45 million, the film will reach theaters in the fall, with a cast that includes Josh Hartnett, Aaron Eckhart, Scarlett Johansson, Hilary Swank and, as the mysterious title lady, Mia Kirshner.

“There aren’t many cases with the mythic quality of the Dahlia,” Mr. De Palma said in a recent interview. “London has Jack the Ripper. America has the Black Dahlia.”

An avid reader of detective fiction and true crime, Mr. De Palma was nonetheless surprised by the public fascination with the Black Dahlia. “There are all these books,” he said. “It just goes on and on. People getting new information, having recovered memories, finding old files and new theories.”

Talking about the lure of Mr. Ellroy’s novel, a dark mystery involving a love triangle and corruption, Mr. De Palma added: “I love all that ’40s stuff, all that noir stuff shot in L.A. — and I haven’t shot too many pictures in L.A. I love to get the characters in the suits and the hats, and I love that great kind of noir cynicism that pervades the Ellroy novels.”

In The Black Dahlia, Mr. Ellroy fictionalized Short in much the same way he transformed real-life characters in his book turned film “L.A. Confidential,” using her murder to propel the novel’s many twists and turns. “I was interested in art and theme,” Mr. Ellroy said, rather than in solving the actual case.

Mr. Ellroy, who was drawn to the Dahlia case as a child through the Jack Webb book The Badge, also became fixated, in large part, because his own mother was murdered when he was 10. “Elizabeth Short and my mother kind of merged,” he said.

“I used to ride my bike” to the Dahlia crime scene, Mr. Ellroy continued. “I started having these horrible nightmares about Elizabeth Short.” (He later examined his mother’s murder in his 1996 memoir, My Dark Places.)

Mr. De Palma’s film is a tangled tale of friendship, love and sexual desire among several Los Angeles detectives and the trio of mysterious women in their lives, and it is just as labyrinthine as Mr. Ellroy’s book. “It is not the story of Elizabeth Short,” Mr. De Palma said, explaining that the Dahlia is shown in flashback. “The movie is complicated. It’s about characters who are impacted and obsessed with what happened to her.”

For the many people who have followed the Dahlia case over the years, Short has been the ultimate mystery woman, representing everything from broken dreams to misogynistic savagery to the lure of unsolved crime.

This much appears to be settled: Elizabeth Short grew up in Medford, Mass., as a free-spirited girl who enjoyed being noticed — and being different.

She was 18 when she moved to the Bay Area to be with her father, who had deserted the family. A month later, she struck out on her own, making her way toward Santa Barbara. For the next few years, she moved between Southern California and Miami, Chicago and Boston. “She always had her suitcase in her hand,” said John Gilmore, whose 1994 book Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder was followed by a wave of books from other armchair detectives. “She was on the move. Not to something, but from something.”

According to reports filed by investigators, Short spent the last five months of her life moving from place to place — at least 11 different residences. One report said “the victim knew at least 50 men at the time of her death.” Frequently spotted on Hollywood Boulevard, and in the company of servicemen, she was not a prostitute. But she was adept at charming men into picking up her tabs. It was a married salesman who dropped her off at the Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, at approximately 10 p.m. on Jan. 9, 1947.

A week later, on Jan. 15, a passer-by spotted what she thought was a mannequin lying in a vacant, weed-covered lot on Norton Avenue, between 39th Street and Coliseum Drive. After moving in for a closer look, the terrified woman called the police.

Officers arrived and found a naked body that had been expertly bisected and drained of blood. The two halves appeared to have been carefully posed, and the victim’s face had been slashed so that the mouth was extended into an eerie smile. There were rope marks on her wrists and ankles, indicating she had been restrained, and other signs of torture.

The photos of Short’s mutilated body and face were considered so shocking that newspapers had to “reconstruct” them, removing signs of violence. It was not until 1984 that several of the unretouched photos appeared in print in Kenneth Anger’s compendium of Hollywood scandals, Hollywood Babylon II. (Nothing shocks anymore: the original photos can now be seen on Web sites, and on coffee mugs and curiosities like a Dahlia snow globe.)

Many theories have emerged about Short’s killing. Were Bugsy Siegel and the mob involved? A drifter named Jack Anderson Wilson? In one book, a former police detective named Steve Hodel posits that his own father, Dr. George Hodel, was the murderer.

Meanwhile, Larry Harnisch, a Los Angeles Times copy editor, has been digging through files, speaking with members of the press-shy Short family and working toward his own hypothesis (and planned book): that the killer was a surgeon named Walter Bayley. It was Mr. Harnisch who cataloged the case files that the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office only recently made available to researchers.

“People love to go through the stuff, but I don’t know if anyone will solve the case,” said Sandi Gibbons, a public information officer for the district attorney’s office. Besides, she said, “There would be nobody around to prosecute, because they’d be dead.”

The files at the Los Angeles Police Department remain off limits even today. “The case is still open,” said Brian Carr, a robbery-homicide detective who calls himself “the keeper of the Dahlia files.”

“I read the letters that come in,” Mr. Carr said. “There’s one guy who uses numerology and triangulation.”

Many would-be detectives inquire about DNA evidence, he added, but “there isn’t any.” The reason: “The body was cleansed.”

As for all the theories, “We aren’t taking any official stance,” he said.

Given its horrific nature and mysterious circumstances, the Dahlia case continues to resonate culturally. Imagery of the case derived from Mr. Ellroy’s writings inspired the jazz composer and saxophonist Bob Belden to write the 12-part musical suite “Black Dahlia.” (Heavy metal has offered up its own homage: a group called the Black Dahlia Murder.) And last year, a Bay Area artist, Hailey Ashcraft, was curator of a multimedia exhibition that explored the mystique surrounding Elizabeth Short. Among the pieces was a photograph of a vacant lot with two abandoned couches.

Mr. De Palma, who is known for exploring dark themes in films like “Scarface,” “Body Double” and “Dressed to Kill,” said he believed that the Dahlia’s mystique was derived from the actual crime-scene photos and those taken by the coroner. “Once you have looked at the real pictures, you never forget the Black Dahlia,” he said. A number of those images appear in the film when one of the characters (played by Mr. Eckhart) plasters them on his wall. “You see them in the background,” Mr. De Palma said. “We don’t move in that close. But what we do see is disturbing.”

For Josh Friedman, the screenwriter, who had the formidable challenge of adapting the 300-plus-page Ellroy novel, his most memorable encounter with Elizabeth Short and her sad story took place a year ago, on the anniversary of her death. Mr. Ellroy, who had come to town to see some friends, invited Mr. Friedman to join them for dinner. “Afterward, we went down to 39th and Norton,” he said. “And James took us to the exact spot where her body was found.”

Asked to recall that night, Mr. Ellroy said: “It was cold. We didn’t get too misty. But I like to check in on her every once in a while.”

Memorials of one kind or another will continue for Short. It couldn’t be any other way. After all, said Mr. Ellroy: “The Dahlia is arguably America’s most celebrated unsolved murder. And a story like no other.”

back to writings

back to writings