The Hypnotic Allure of ‘Nightmare Alley’

Mystery Scene, Spring 2019

The opening music is lush but ominous. As the movie credits roll, strains of carnival music break through, accompanying the camera as it moves in on a barker, doing his best to entice crowds outside a tent with a sign that reads GEEK.

GEEK? To modern audiences, a geek is someone with minor social skills – possibly combined with extra-ordinary intelligence. An eccentric. An oddball. A dweeb.

Back in the 1940s the term implied something else – something dark. And tragic. Something within this movie tent, where a striking looking man, wearing a white T-shirt and great physique, watches and waits. “This exhibit is being presented solely in the interest of education and science!” claims a handler, who points to an unseen figure below. “Is he the missing link? Is he man or beast?”

The man in the T-shirt – his name is Stanton Carlisle, and he’s a newcomer to the carnival biz – stands, appalled, among the gaping onlookers. When the (unseen) geek is tossed live chickens to eat, Carlisle walks away from the squawks of brutalized poultry, and the resulting gasps from the crowd. He goes on to say, incredulously, “I can’t understand how anybody could get so low.”

It’s a prophetic line that serves as a dirty welcome mat to “Nightmare Alley,” a weird, unsettling 1947 movie about an enigmatic grifter who uses the women he meets to con his way to the top.

The movie, and the eponymous 1946 book on which it’s based, have become known for a haunting mystique, spilling out over various incarnations.

There have been myriad critical analyses, a graphic novel adaptation, a musical stage production, and reports of planned film remakes – the latest of which involves Academy Award-winner Guillermo Del Toro. With its saga of deceit and lies and a central destructive character who appears irredeemable, it has also become a go-to attraction for mystery and crime enthusiasts.

Why? Give the geek some of the credit. Until “Nightmare Alley,” the general public wasn’t aware of the term, or the carny practice of exhibiting a man sunk to his lowest depths, a victim of alcohol abuse.

There is also the story’s grim trajectory, as Stan Carlisle goes from carnival mind reader to tuxedo-clad nightclub “mentalist,” with the help of a stolen “word code.” He’s poised to become the spiritual leader of his own church when karma closes in. At book and film’s end – Spoiler Alert – it’s Carlisle who is the geek.

The downbeat mood and fatalistic characters ushered the movie into the film noir canon, despite it not fitting the genre’s traditional model.

And then there is the head-spinning story of the book’s author. The rise and fall of William Lindsay Gresham is nowadays seen as a parallel to the story of his fictional charlatan, Stanton Carlisle. “It was a case of life reflecting art and art reflecting life,” says Alain Silver, a Los Angeles filmmaker and film historian-author who, with writing partner James Ursini, has written extensively about film noir. (Their latest work is “Film Noir Prototypes: Origins of the Movement,” for Applause Books.)

“He had this urge to expose the hidden side of things. He was in search of truth and enlightenment. But, deep in his heart, he knew he was never going to find it,” says Bret Wood, an Atlanta-based filmmaker who wrote the introduction to a 2013 collector’s edition of “Nightmare Alley” and edited a 2014 anthology of Gresham’s writings, both for Centipede Press.

Born in Baltimore, William Lindsay Gresham mostly grew up in New York, where he prowled the sideshows of Coney Island. He was 29 and serving with the army of the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War, when he struck up a friendship with a medic who was an old carny man. He told Gresham about “the geek” – carnival slang for an act in which a man bites the heads off live chickens or other small animals. “Where do you get a geek?” Gresham asked. The answer: “You don’t get a geek. You make one.” With an assist from booze.

Gresham’s longtime interest in carnivals, and the geek, were the genesis of “Nightmare Alley.” Nothing else that he wrote, including a second novel and a spate of non-fiction articles, came close to its success or infamy.

Charles Schlessiger, now 85, was the agent who oversaw subsidiary rights for the author’s literary agency, Brandt and Brandt (now Brandt and Hochman). “I remember Bill as a nice guy who was kind of lighthearted. The last time I saw him, he said something funny to me. Don’t ask me what it was, it was too long ago. I do remember that the next thing I knew, I heard he’d committed suicide. And I just couldn’t figure that out.”

”Remember,” Schlessiger says, “The book is a classic in the truest sense. Think about it. Since 1946 it’s never been out of print.”

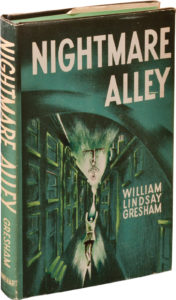

First published in September 1946 by Rinehart and Company (at a cover price of $2.50), “Nightmare Alley” had such sensational, sordid subject matter it was a guarantee to be noticed.

The pulpy storyline – with chapters named for the various tarot cards – is populated by a bevy of unusual characters: a fake mind reader, who believes in the power of the tarot, and her drunken husband; a sweet young thing who falls under Carlisle’s spell; a midway strongman; and a female psychologist who spots Carlisle for what he is (because it takes one to know one). She’s put together a high society Chicago clientele, incredulous dupes for what she and Carlisle call “the spook racket,” the use of tricked-out spiritualism to contact loved ones in the hereafter. But Instead of leading to money and power, the gambit results in a dour finale – just as the tarot cards predicted.

And, of course, there is Carlisle. As he confesses to the psychologist Lilith, “I’m a hustler, God damn it … I’m on the make. Nothing matters in this damned lunatic asylum of a world but dough … When you get that you’re the boss … I’m going to milk it out of those chumps and take them for the gold in their teeth before I’m through.”

No wonder the Philadelphia Inquirer dubbed it a “fascinatingly evil novel” and said Carlisle “muscles himself into a sure niche of immortality in the anteroom, at least, of literature’s Hall of Infamy.” The Montgomery (Alabama) Advertiser warned, “Eyebrows will be raised higher than a cat’s back at this profoundly shocking and evil novel.” The headline in the Atlanta Constitution read, Beware Geeks Bearing Gifts. The review wrapped with, “… if you like your meat raw, it should be your dish.”

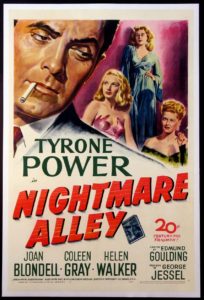

These headline grabbing reviews caught the attention of a man who would seem to be least likely interested – one of vaudeville’s most beloved comedians. George Jessel, the actor-humorist known as “the nation’s foremost toastmaster,” took the project to 20th Century-Fox, where he had produced the frothy movie musicals “The Dolly Sisters” and “I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now?” He got studio chief Darryl Zanuck to buy the book’s rights for $50,000.

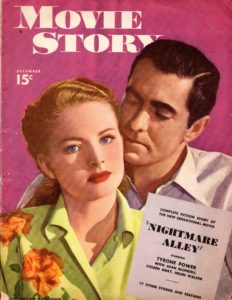

Enter one of Hollywood’s most dashing leading men, Tyrone Power. Known for his dark, swoon-worthy good looks and for playing smooth romantic leads – often in period costume, with sword in hand – Power was searching for an image change. He’d already taken a serious step with his most recent release, in which he starred as a World War I veteran in search of spiritual enlightenment, in Fox’s adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s “The Razor’s Edge.”

Enter one of Hollywood’s most dashing leading men, Tyrone Power. Known for his dark, swoon-worthy good looks and for playing smooth romantic leads – often in period costume, with sword in hand – Power was searching for an image change. He’d already taken a serious step with his most recent release, in which he starred as a World War I veteran in search of spiritual enlightenment, in Fox’s adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s “The Razor’s Edge.”

In an oft-quoted Fox publicity release for “Nightmare Alley” Power said, “Stan Carlisle fascinated me. He was such an unmitigated heel … Here was a chance to create a character different from any I had ever played before.” Flexing his movie star muscle, Power convinced Zanuck to hire his “Razor’s Edge” director, Edmund Goulding, to helm the picture. Jules Furthman (“To Have and Have Not,” “The Big Sleep”) came aboard as screenwriter. Gresham was reportedly a consultant (though what he did, exactly, has never been authoritatively recounted).

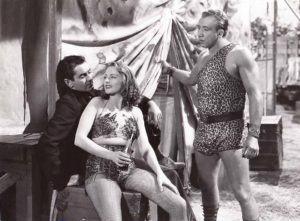

Joan Blondell, who possessed an earthy allure even at age 41, was cast as Zeena, the sham mind reader. Starlet Colleen Gray was chosen for the virginal carnival gal, Molly. Helen Walker, known for playing home wreckers, brought her chilly presence to the role of psychologist (and femme fatale) Lillith. (The movie Lillith spells her name with two “l’s.”) Rounding out the cast were veteran character actors Mike Mazurki, known for a string of thug-type roles, as Bruno the strongman; Ian Keith as Zeena’s boozy, doomed husband, Pete; and Taylor Homes as Ezra Grindle, a wealthy man who becomes one of Carlisle’s suckers.

Joan Blondell, who possessed an earthy allure even at age 41, was cast as Zeena, the sham mind reader. Starlet Colleen Gray was chosen for the virginal carnival gal, Molly. Helen Walker, known for playing home wreckers, brought her chilly presence to the role of psychologist (and femme fatale) Lillith. (The movie Lillith spells her name with two “l’s.”) Rounding out the cast were veteran character actors Mike Mazurki, known for a string of thug-type roles, as Bruno the strongman; Ian Keith as Zeena’s boozy, doomed husband, Pete; and Taylor Homes as Ezra Grindle, a wealthy man who becomes one of Carlisle’s suckers.

Production took place in mid-1947. For authenticity, Fox hired an actual carnival. Its attractions spilled out over 10 acres of the studio’s backlot.

Three veteran carny men worked as consultants on “Nightmare Alley.” One of them, Ed Mundy, praised the movie’s sideshow performers while lamenting how changing times had impacted the business. Speaking to the Los Angeles Herald-Express, he said, “Today about the only top freaks are the sheep-headed boys, Eko and Iko.” (The wild-haired siblings were actually Albino African-Americans.) Added Mundy, at a time that pre-dated political correctness, “Improved health standards in the country are wiping out the monstrosities.”

As for the film’s beautiful people, Fox bragged about Power’s 28 (count ‘em) love scenes with his three leading ladies.

Still, Zanuck was worried. Studio memos of story conferences reveal his concern that the various screenplay outlines lacked “a sympathetic character to root for.” He also wanted the sexual content toned down, and a less hopeless ending.

Zanuck got what he wanted. In the book, Stan Carlisle is sexually involved with Zeena, Molly and Lillith. In the film he appears to be faithful to Molly – whom he’s forced to marry (presumably after having bedded her) – while involved in his shady dealings with Lillith. And unlike the book, which ends with Molly remarried, at film’s end she’s there to care for Stan.

**

When the movie opened that October some critics lobbed metaphorical tomatoes.

“The irritating deficiency about “Nightmare Alley” is its shocking lack of good taste,” opined the New York Times’ Bosley Crowther. The New York Daily News called it “too unpleasant to warrant a hearty endorsement.”

Most everyone, however, singled out Power’s take-no-prisoners performance. Comparing the star’s work in “The Razor’s Edge” to that of “Nightmare Alley,” the Los Angeles Times’s Philip K. Scheuer noted, “Power is much more convincing as a phony spiritualist than he was as the real thing.”

Most everyone, however, singled out Power’s take-no-prisoners performance. Comparing the star’s work in “The Razor’s Edge” to that of “Nightmare Alley,” the Los Angeles Times’s Philip K. Scheuer noted, “Power is much more convincing as a phony spiritualist than he was as the real thing.”

Nor were there complaints about production values. Not with cinematography by Lee Garmes, master of lighting, or the mournful music by Cyril Mockridge.

The trade publication Hollywood Reporter even called it “one of the finest pictures of the year,” and predicted an Academy Award nomination for Power. (It didn’t happen). Variety was cautious: “[The film] at times has the eerie effect of a horror film and occasionally approaches authentic tragedy … [but] one guess is as good as another as to what it will do at the box office.”

The industry seer got that right. Despite its A-ticket star and classy production, the movie’s box office sales wound up on the lower rung of the year’s Top 100 movies. Five years after the movie’s release, as Power exited Fox after a lengthy contract, he was asked to name his favorite film. He quickly cited “Nightmare Alley,” adding, “The studio did nothing to sell it and it wasn’t a success.”

**

Though “Nightmare Alley” was reissued theatrically in the early 1950s, to run as the second string title on double bills, it was its end-of-the-decade sale to television that insured its resurrection.

It first surfaced on TV in 1959. Per an early log line: “An ambitious but ruthless barker for a traveling carnival steals a wife and an act.” As the movie continued to air, in markets across the country, programmers – and the critics who worked for the papers that printed the log lines – reconsidered the film. The log lines became more enticing. As in, “Carnival man becomes obsessed with greed and turns himself into a mental monster” … “A carnival clairvoyant wreaks a terrible vengeance on himself” … “Strong drama about a carnival drifter who double crosses everybody on his way to success. One of Power’s best performances. Very good.”

Then there was the one that wrapped with, “This is one of the eeriest pictures of all time.”

That reputation continued to grow, with an assist from fans of offbeat cinema – which was becoming a kind of genre all its own. Bill Landis, a New Yorker who proudly prowled the theaters of then-scary Times Square, touted “Nightmare Alley” as a “sleaze” film in his self-published Eighties fanzine Sleazoid Express. As Landis told the Los Angeles Times, “I loved the attitude … that all people are sick, venal and greedy.” The movie got a listing in “The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film” (1983), which celebrated “the wildest movies ever made!!” And befitting its growing fandom, it was included in cult movie compendiums.

Thanks to 16-millimeter rentals, it also became a staple of screenings sponsored by film societies and college campuses.

That market ultimately died, replaced by the home viewing market made possible by the development of the video cassette. But there never was a VHS release of “Nightmare Alley,” due to a protracted lawsuit between the estate of producer George Jessel and Fox. This further fueled the want-to-see factor for the film.

“It was one of those films that people taped, if they got the chance. And then they passed around those tapes. And the movie got this mythic reputation,” says Bret Wood.

As bootleg video copies showed up for sale on eBay, the film’s only surviving star, Colleen Gray, graciously greeted fans at film festivals and fan gatherings. At retrospective houses the movie was sometimes co-billed with Tod Browning’s “Freaks,” the still-disconcerting 1932 film about human oddity sideshow performers. By this time “Nightmare Alley” was being promoted as film noir.

**

Hardboiled American crime fiction – the kind with tough guys, tougher dames, gunplay and shadowy streets (think Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade) – helped give rise to the noir genre. So did the gloomy tone of those works.

Those elements were plenty visible in 1947, when the marquees featured titles such as “Out of the Past,” “Body and Soul,” “Crossfire,” “Dark Passage,” “Kiss of Death” and “The Lady from Shanghai.” “Nightmare Alley” didn’t fit the mold – but it had fatalism to spare. It was also that rare movie experience that wasn’t easily forgotten.

“It’s not your typical crime-pulp piece. But it’s the spirit of film noir in a setting you don’t really associate with crime,” says Wood, adding, “Also, you can’t underestimate the power of the geek.”

“It’s kind of a fractured noir,” admits Silver. “The film examines transcendental philosophy and it’s got a somewhat redemptive ending. Instead of a crime setting we’ve got a carnival, which takes us, at least in the first half of the story, into a kind of secret society. Within it you have these outlandish characters, and within that context Stan appears to be normal. Only you find out he’s anything but.”

Prolific author/interviewer Tom Weaver, known for his more than three dozen books focusing on the science fiction/horror genres, finds elements of the latter in “Nightmare Alley.” “It’s such a unique picture to come out of 1940s Hollywood. It’s like it’s a pre-Code film made in 1947,” he said, referencing the Production Code, which brought censorship guidelines to films produced after the mid-1930s. Adds Weaver: “The film is so incredibly dark, so pessimistic. It’s even got a steak of meanness in its casting of Ian Keith as a drunk (as the husband of mind reader Joan Blondell), because he really was a drunk. Drinking ruined his career.”

**

“Nightmare Alley” was finally released on DVD in 2005, with commentary by Silver and Ursini.

The story has since materialized in different mediums.

A stage musical, by playwright Jonathan Brielle, premiered in 2010 at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles. The two-act production, which included the musical numbers “Tough Cookies,” “The Code” and “Whatever It Takes,” was later performed Off-Broadway.

A graphic novel by the late underground comix artist Spain, aka Spain Rodriguez (aka Manuel Rodriguez) was published in 2003 by Fantagraphics Books. Time magazine loved it. “Not so much a yarn as a boiled leather strap … This is no ‘Hey! Rube!’ Go check it out.”

There’s also talk of a remake. Again.

Back in the late Seventies, it was music mogul Berry Gordy – legendary founder of the Motown label – who planned to direct a version starring Billy Dee Williams.

Currently, it’s Guillermo Del Toro – who won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director for “The Shape of Water” – with a planned remake on the boards.

The book, meantime, is currently published by New York Review Books Classics, with an introduction by Nick Tosches, the novelist-biographer known for his philosophical riffs. It is also included in the prestigious Library of America collection, “Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s and 40s.”

**

As for Gresham: his personal story included a stint as a folksinger, suicide attempts (he once attempted to hang himself, but the hook broke), and much-written-about marriage to Joy Davidman, a poet whose writings also included feminist-leaning film reviews.

The pair had shared interests, including political activism (they both joined the Communist Party), spiritual growth (they tried various religions, including Dianetics, which gave rise to Scientology), and a love of cats. They were parents of two young sons. But they both struggled professionally.

Gresham, who wrote for the pulps and men’s magazines before hitting pay dirt with “Nightmare Alley,” would publish only one more novel, 1949’s tepidly received The Tower, set in a TB hospital. Then came “Midway Monsters,” a collection of his non-fiction writings, followed by a biography of Houdini. Oddly, his final book was about body building.

Gresham, who wrote for the pulps and men’s magazines before hitting pay dirt with “Nightmare Alley,” would publish only one more novel, 1949’s tepidly received The Tower, set in a TB hospital. Then came “Midway Monsters,” a collection of his non-fiction writings, followed by a biography of Houdini. Oddly, his final book was about body building.

His personal life took a curious twist when Davidman met the British writer and theologian C.S. Lewis (“Chronicles of Narnia”). She subsequently divorced Gresham and married Lewis, an unlikely romance that was the basis of the 1993 film “Shadowlands,” starring Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger.

Gresham, meantime, married Davidman’s cousin, while continuing a spiritual search that sometimes veered into the occult.

He was 53 and suffering from cancer of the tongue in September 1962 when he checked into New York’s Hotel Dixie, where he’d written much of “Nightmare Alley.” Registered under one of his pseudonyms, he took an overdose of sleeping pills.

In the years since, many “Nightmare Alley” admirers have sought to understand Gresham, a man who once said, “Perhaps we are all freaks, doing the best we can with the handicaps we carry through the world.”

back to writings

back to writings